If you’ve ever lived with depression, you know how big of an impact it can have on all areas of your life, from relationships, to work, to sleep. For many people, this depressive state is cyclical and occurs throughout the year, depending on the season.

If this sounds familiar, you may be dealing with seasonal affective disorder (SAD), or seasonal depression. What exactly is SAD, though? How does it impact sleep and energy levels? Perhaps most importantly, how can you get to feeling better? Here, we’ll answer these questions and more.

What Is Seasonal Affective Disorder?

Seasonal affective disorder, also referred to as seasonal depression, is a type of recurring depression with a seasonal pattern. As summer turns into fall and winter, the temperature drops, and the hours of sunlight decrease. For as many as 10 million Americans1, these changes trigger symptoms of depression that aren’t present at other times during the year.

SAD is different from major depression in that it comes and goes at roughly the same time every year. These symptoms can be so severe that they interfere with daily life and may even increase the risk of suicide2.

A milder form of the disorder, known as subsyndromal seasonal affective disorder (S-SAD), is also referred to as the “winter blues3”. For this group of men, women, and even children, the winter blues may come and go but only cause small changes in things like mood, appetite, and energy.

Though most people experience SAD as the weather transitions into the colder months, some may experience this in the spring or early summer. While people who experience seasonal depression in the winter tend to get excessively sleepy, people who experience it in the warmer months tend to experience the opposite: insomnia.3

Researchers believe this is because of the temperature and sunlight during these times of the year. This is why SAD is less common in sunny, warm places like Florida and occurs at higher rates in dark and cool places like Alaska. Risk factors include being female, being younger, living farther from the equator, and having a family history of depression, bipolar disorder, or Seasonal Affective Disorder[3].

The criteria4 for seasonal depression, as set in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), is depression that starts and ends during a specific time every year with full remission during other seasons. These symptoms must last for at least two years with more seasonal episodes of depression than seasons without it over time.4

Winter and Summer Symptoms of Seasonal Affective Disorder

For people living in northern climates, the winter blues can be commonplace. While S-SAD can bring on small changes in mood and affect, the temporary symptoms are mild and can be managed with lifestyle changes like exercise, self-care, and meditation.

For those battling seasonal affective disorder, the symptoms are similar to major depression, affecting nearly every aspect of life. The two most common symptoms of SAD are low energy and a depressed mood, regardless of which variation occurs.

Those experiencing a winter seasonal pattern may also have the following symptoms:

- Sadness

- Irritability

- Frequent crying

- Fatigue and lethargy

- Difficulty Concentrating

- Sleeping more than normal

- Lack of energy

- Decreased activity levels

- Withdrawing from social interactions (hibernation)

- Craving sugar and carbohydrates

- Weight gain

On the other hand, those experiencing the summer variation may have these symptoms:

- Irritability

- Poor appetite

- Weight loss

- Insomnia

- Agitation

- Restlessness

- Anxiety

- Episodes of violent behavior

People with depression, bipolar disorder, or other mental health disorders may also be affected by the changing seasons with a worsening of symptoms during the winter months. Bipolar disorder5 is characterized by alternating patterns of mania and depression, and many individuals with this disorder experience depressive lows during the winter months with manic highs during the summer.

Tips for Sleeping Better in the Winter

Winter blues or not, getting adequate sleep in this cold and dark season can be a challenge. If you feel tired and lethargic, you may not be sleeping enough or getting the restorative rest you need. Here are some tips on how to sleep better in the long, winter months:

Light Therapy

Light therapy utilizes light boxes or specially designed LED lights to improve depression. These boxes, most small enough to sit on the counter, emit full-spectrum rays, similar to sunlight. Using them for just 20 to 60 minutes a day each morning from early fall until spring may help lower the increase mood-boosting chemicals and hormones, which could translate to better sleep at night.

To date, light therapy has been the most widely studied treatment for seasonal affective disorder. In a review6 of studies of light therapy, early morning treatment with an average dosage of 2,500 lux daily for one week resulted in a significant amount of remissions in depression symptoms.

Learn More: Best Light Therapy Lamps

Spend Time Outside

Artificial lights can be helpful, but natural sunlight is best. If you live in a place where there is sunlight during the day and temperatures are safe to be outside, spending time outside in the sun is a great way to boost your mood and get vitamin D, which helps battle depression. Similar to light therapy, this can help regulate depression symptoms as well as your body’s circadian rhythm.

Exercise Regularly

Exercise has some amazing benefits for sleep. Working out triggers the release of endorphins and other chemicals that make you feel good, and it can help you to sleep better at night. Bonus points if you can exercise outdoors in the natural sunlight.

Relaxation Techniques

Yoga, meditation, and deep breathing are all effective ways to calm the body and mind. In the morning, they can help you feel focused and more energized for the day. In the evening, they can clear the mind from all the worries of the day so you can focus on the most important task at hand – sleep.

Maintain Regular Sleep and Wake Times

One of the most underestimated yet effective ways to improve sleep is by sticking to a regular schedule when it comes to sleep and wake times. Going to bed and waking up at the same time every day, including weekends, helps to establish a pattern and balances the body’s internal master clock. Over time, maintaining this routine may help you to wake up feeling more alert and cut down on the time it takes to fall asleep at night.

Here are some good places to start:

- 9 Simple Nighttime Rituals To Help You Relax and Unwind

- 9 Tips On How To Wake Up Early – Start a New Routine Today

Causes of Winter Seasonal Depression

Scientists are still trying to understand the complexities of mood changes over the winter months. They haven’t been able to pinpoint one distinct cause, but there are some biological explanations that they’ve been able to uncover. Blaming it all on the lack of sunshine may seem overly simple, but natural light exposure does play a significant role.

Difficulty Regulating Serotonin

If you’ve ever taken an antidepressant, you may have heard the term “SSRI”. This stands for “Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors”. These medications work by increasing the amount of serotonin in the brain, thus helping to balance mood.

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that’s found in the brain and gut and is involved in regulating mood. Neurotransmitters are chemicals that act as messengers, relaying information from nerves to other nerves, muscles, or throughout the body.

Researchers7 have discovered that people with SAD may have difficulty regulating serotonin. SERT is a protein that transports serotonin, and when there are higher levels of this protein, less serotonin is available, leading to depression. Sunlight plays an important role in keeping SERT levels low, so when fall and winter come, serotonin levels drop.

Excessive Melatonin Production

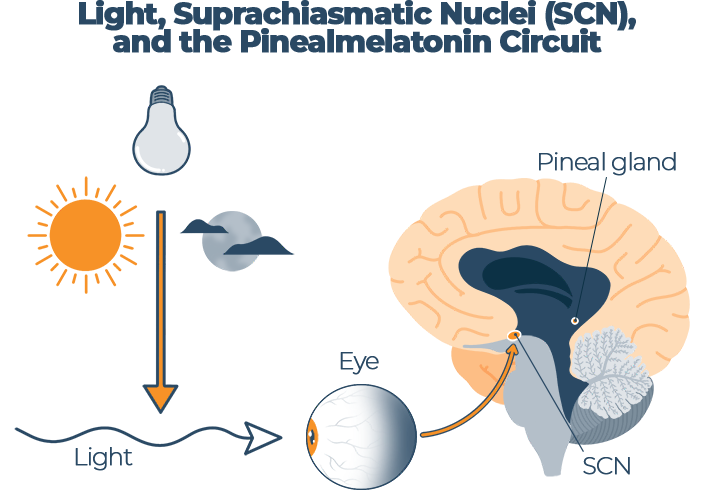

Melatonin is a hormone that plays an important role in regulating the sleep-wake cycle, aka the circadian rhythm. To understand how light controls melatonin production, we need to jump into the brain to look at a tiny pea-sized structure known as the pineal gland.

The pineal gland is responsible for creating melatonin, the hormone that makes you feel tired. The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) is a tiny part of the brain in the hypothalamus that tells the pineal gland when and how much melatonin to make. The SCN does this based on the information it receives from receptors in the eyes.

Source: “Melatonin as a potential anticarcinogen for non-small-cell lung cancer8”, Oncotarget

Natural sunlight helps to regulate this master alarm clock, relaying information about whether it’s day or night. Unfortunately, according to the Environmental Protection Agency9, Americans spend over 90 percent of their time indoors, especially during the long and dark winter months.

Research10 has shown that people with seasonal affective disorder may produce excessive amounts of melatonin. This could explain why they feel excessively tired and sluggish during the winter months, often spending more time in bed.

Lower Vitamin D Levels

Another downside to spending so much time indoors is that the skin misses out on the sun exposure it requires to produce vitamin D.

Vitamin D has many different functions, and one is its involvement in serotonin activity. You only need 5 to 30 minutes11 of sun exposure to the face, arms, legs, or back without sunscreen between 10:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m. twice a week to get sufficient vitamin D, but most people aren’t even getting this. A detailed examination12 of National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys from 2001 to 2004 discovered that 77 percent of the U.S. population is deficient in vitamin D.

Many people living in northern climates have lower levels of vitamin D over the winter months, and they may be encouraged by their healthcare providers to take a vitamin D supplement during this time. Research13 has also discovered that people with SAD may produce less vitamin D, and a deficiency of this vitamin has been linked to depression.

Circadian Rhythm Delay

The winter months bring less light exposure, which we’ve identified as a key factor in regulating the body’s circadian rhythm. Increased melatonin and decreased serotonin can have a huge impact on this internal 24-hour sleep-wake clock.

For this reason, people with SAD often have a circadian rhythm delay. Research has discovered that “the circadian signal that indicates a seasonal change in day length has been found to be timed differently, thus making it more difficult for their bodies to adjust.”3

In one study,14 people with seasonal affective disorder had circadian rest-activity rhythms that were delayed by up to 70 minutes compared to healthy controls.

Another study15 examined whether the circadian pacemaker in patients with SAD signals a change in day length after the transition from winter to summer. They discovered that “patients with seasonal affective disorder generate a biological signal of change of season that is absent in healthy volunteers and that is similar to the signal that mammals use to regulate seasonal changes in their behavior.”

The problem with this signal in humans is that we don’t hibernate like other mammals. Healthy individuals don’t have this signal, so it could be part of the reason people with SAD react differently to the change in season.

Winter Insomnia

While most individuals with winter-onset SAD experience excessive fatigue and sleep, there are some who have the opposite problem. Several studies16 in northern countries have found that the darker winter months are associated with poor sleep.

One study17 compared sleep and mood in people living in two drastically different areas of the world where there is a great variation in sunlight throughout the seasons. In Ghana, where the duration of daylight remains constant, there was hardly any difference in sleep or mood throughout the winter months. In Norway, where there is a lack of daylight over several winter months, individuals reported insomnia, fatigue, and depression.

More and more research is looking at the close connection between mood and sleep. Many people with depression report insomnia and other sleep disturbances, and scientists have identified that the part of the brain that regulates sleep is also closely tied to mood. A review18 done in 2013 found that the majority of those with mood disorders also have circadian rhythm disturbances affecting their sleep and wake cycles.

Another factor that may play a role in winter insomnia is the great amount of time spent indoors. For most people, most of this time is spent in front of electronics like phones, computers, and televisions, all of which emit primarily blue light. This is one of many wavelengths of light that the sun naturally emits, but in our blue-lit 21st-century world, we’re being bombarded with round-the-clock blue light.

While some blue light is beneficial, too much of it could be negatively impacting our health. Research19 has shown that blue light directly inhibits our body’s melatonin flow, hurting our ability to fall asleep in addition to negatively impacting the quality of the sleep we get.

If you are having trouble with insomnia, here is a list of best mattresses for insomnia, that can be of help when dealing with it.

Daylight Savings and Seasonal Depression

Daylight savings occurs twice a year, once in in the spring and again in the fall. During the spring, we move our clocks ahead an hour, and in the fall, we move them back an hour.

Unfortunately, the practice of daylight savings causes disruptions to the circadian rhythm that have been shown to have multiple adverse effects. Research20 has found that daylight savings time transitions are associated with sleep disturbances, fatal car accidents, and increased heart attacks and strokes the day after the spring time change.

In a 2017 study21, a team of international researchers looked at 185,419 Danish hospital intake records between 1995 to 2012 where there was a diagnosis of depression. These Danish scientists discovered that during the transition from summertime to standard time (known as “fall back”), there was an 11 percent increase in depressive episodes.

The researchers concluded that “the observed association is primarily related to the psychological distress associated with the sudden advancement of sunset from 6 PM to 5 PM, which marks the coming of winter and a long period of short days.” They believe that the majority of these individuals likely had seasonal depression in the past and that the sudden shift to less evening daylight served as an omen of the dark season ahead.21

While the idea behind moving the clocks back in the fall is to provide more early morning sunlight, which should be beneficial for those with depression, the opposite may be true for those with SAD. Dr. Norman Rosenthal is a Psychiatrist and was one of the original doctors who first described seasonal affective disorder in 1984.

Dr. Rosenthal explained the negative effects of daylight savings (“fall back”) in an article published in the Chicago Tribune22 where he was quoted saying, “When the clocks turn back, that’s supposed to give you an extra hour of light in the morning. But people with seasonal affective disorder typically have a hard time getting up in the morning. So light is being given back to them when they have the comforter over their heads, and then it gets dark in the afternoon when people with SAD are most likely more active.”

Conclusion

If you have the winter blues, it may be tempting to just pack your bags and move south. Unfortunately, this type of major life change isn’t always feasible. Seasonal depression is a real disorder, and it’s important to seek treatment.

As we’ve seen in the research, it can impact every area of your life, including sleep. Thankfully, there are so many promising treatments that can help. If you’re struggling, remember that you’re not alone — find a friend, loved one, or trusted medical professional to speak with today so you can embark on your journey to feeling whole again.

Raina Cordell

RN, RHN, Certified Health Coach

About Author

Raina Cordell is a Registered Nurse, Registered Holistic Nutritionist, and Certified Health Coach, but her true passion in life is helping others live well through her website, www.holfamily.com. Her holistic approach focuses on the whole person, honing the physical body and spiritual and emotional well-being.

Combination Sleeper

References

- O’Keefe, Madeleine. “Seasonal Affective Disorder Impacts 10 Million Americans. Are You One of Them?”. Boston University. 2019.

- Praschak-Rider, Nicole., et. al. “Suicidal Tendencies as a Complication of Light Therapy for Seasonal Affective Disorder: A Report of Three Cases”. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1997.

- Melrose, Sherri. “Seasonal Affective Disorder: An Overview of Assessment and Treatment Approaches”. Depression Research and Treatment. 2015.

- Halverson MD, Jerry L. “Depression Clinical Presentation”. Medscape. Last modified August 29, 2024.

- Bullock, Ben., Murray, Greg., Meyer, Denny. “Highs and lows, ups and downs: Meteorology and mood in bipolar disorder”. PLoS One. 2017.

- Terman, M., et al. “Light therapy for seasonal affective disorder”. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1989.

- “Seasonal Affective Disorder”. National Institute of Mental Health. Webpage accessed December 7, 2024.

- Ma, Zhiqiang., et. al. “Melatonin as a potential anticarcinogen for non-small-cell lung cancer”. Oncotarget. 2016.

- “Indoor Air Quality”. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Last modified September 7, 2021.

- Lewy, Alfred J., et al. “The circadian basis of winter depression”. PNAS. 2006.

- Nimitphong, Hataikarn., Holick, Michael F. “Vitamin D status and sun exposure in southeast Asia”. Dermato-endocrinology. 2013.

- Ginde MD, Adit A., Liu MD, Mark C., Camargo Jr. MD, Carlos A. “Demographic Differences and Trends of Vitamin D Insufficiency in the US Population, 1988-2004”. JAMA Network. 2009.

- Anglin, Rebecca E.S., et al. “Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis”. Cambridge University Press. 2018.

- Teicher MD, Martin H., et. al. “Circadian Rest-Activity Disturbances in Seasonal Affective Disorder”. JAMA Network. 1997.

- Wehr MD, Thomas A., et. al. “A Circadian Signal of Change of Season in Patients With Seasonal Affective Disorder”. JAMA Network. 2001.

- Suzuki, Masahiro., et. al. “Seasonal changes in sleep duration and sleep problems: A prospective study in Japanese community residents”. PLoS One. 2019.

- Friborg, Oddgeir., et al. “Associations between seasonal variations in day length (photoperiod), sleep timing, sleep quality and mood: a comparison between Ghana (5°) and Norway (69°)”. National Library of Medicine. 2012.

- McClung PhD, Colleen A. “How might circadian rhythms control mood? Let me count the ways”. Biological Psychiatry. 2013.

- Tähkämö, Leena., Partonen, Timo., Pesonen, Anu-Katriina. “Systematic review of light exposure impact on human circadian rhythm”. National Library of Medicine. 2018.

- Sandhu, Amneet., Seth, Milan., Gurm, Hitinder S. “Daylight savings time and myocardial infarction”. BMJ Journals. 2013.

- Hansen, Bertel T., et. al. “Daylight Savings Time Transitions and the Incidence Rate of Unipolar Depressive Episodes”. Epidemiology. 2017.

- Dampier, Cindy. “The end of daylight saving time can mark the start of seasonal depression. Here’s how to head it off (hint: no sleeping late)”. Chicago Tribune. 2019.